JCN supplement

2018,Vol 32, No 2

9

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

GRADING EVIDENCE

The grading and presentation of

evidence for clinical implementation

has developed in two directions:

An extensive critical appraisal of

all the published and presented

information on a subject, but

which only includes RCTs

with clear definitions, blinding

and randomisation, in any

final study. An example is the

Cochrane systematic review

on compression for venous

leg ulcers (Cullum et al, 2009,

updated from 2001)

An approach that focuses not

only on level 1 evidence, such

as RCTs, but includes all levels

of evidence, for example

guidance from the National

Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE) (Leaper,

2009). An example in wound

care includes the NICE (2008)

study, ‘Surgical site infection:

prevention and treatment of

surgical site infection’.

The second of these approaches

involves interested clinicians and

scientists who analyse the available

evidence. The evidence is still

graded for its level of excellence,

but this approach allows experts

to formulate clinical guidelines,

particularly in the absence of high-

level evidence. In a field such as

wound care where the amount of

level 1 evidence is small, guidelines

supported by expert opinion are

critical to support and improve

wound care practice.

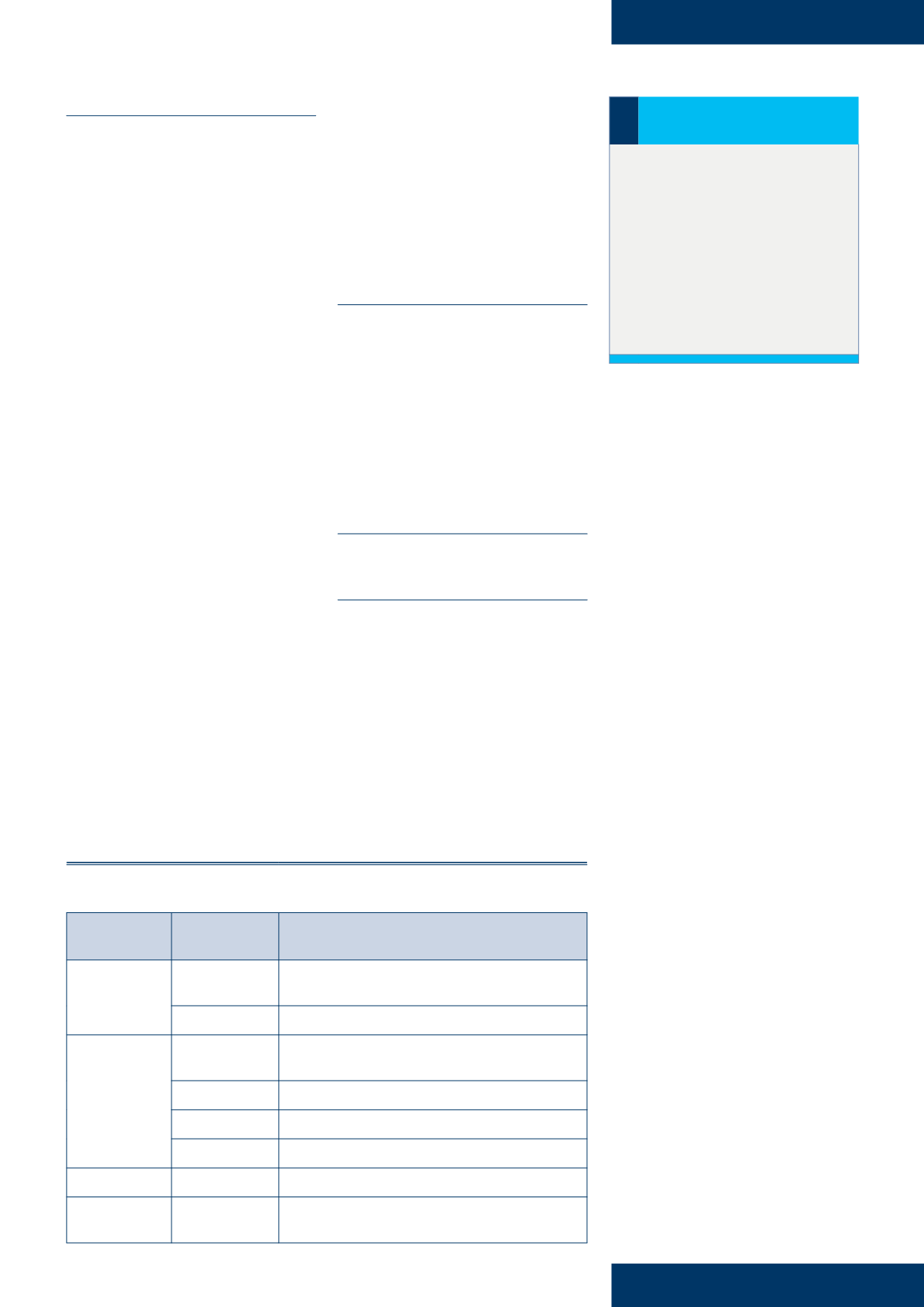

When all levels of evidence have

been included in the review, they

will usually be graded in terms of

recommendations for practice, i.e.

from A–D, with recommendation A

being the highest (

Table 1

).

However, lack of knowledge is

not an excuse for a nurse failing to

provide the patient with the best

possible wound care and, if a nurse

was to be challenged about poor

care, it would not provide a robust

defence. Therefore, nurses treating

wounds need to ensure that their

knowledge and practice are based

on the most up-to-date evidence.

Where barriers exist, they need to be

identified and raised as a concern or

a patient safety issue.

The wound management

literature includes a confusing

array of tools, models, evidence-

based protocols, guidelines and

algorithms, which are all aimed at

improving clinical decision-making

(Flanagan, 2005). However, if these

guidelines are to be practically

applied, they need to appraised,

made simple, and contextualised

for practice. Local tissue viability

specialists and link nurse support

groups can make a valuable

contribution to ensuring evidence-

based practice becomes a reality

and can provide a good source of

knowledge for community nurses.

Dressing manufacturers should

also be able to supply a summary

of available research for individual

products; the nurse can then

draw conclusions about the level

of evidence presented using the

hierarchy of evidence model

(

Table 1

).

There are a number of strategies

that can be used to support the

implementation of research evidence

into practice and effective models

include the five-step process, which

is often referred to as the 5As and is

Table 1:

Study design and level of evidence with grade of recommendation (Oxford Centre for

Evidence-based medicine, 2001)

Grade of

recommendation Level of evidence Type of study

A

1a

Systematic review of (homogeneous) randomised controlled

trials (RCTs)

1B

Individual RCTs (with narrow confidence intervals)

B

2a

Systematic review of (homogeneous) cohort studies of

‘exposed’and‘unexposed’subjects

2b

Individual cohort study/low-quality RCTs

3a

Systematic review of (homogeneous) case control studies

3b

Individual case control studies

C

4

Case series, low-quality cohort or case control studies

D

5

Expert opinion based on non-systematic reviews of results or

mechanistic studies

‘Evidence is of little benefit

to the patient unless it is

implemented in practice.

There are many challenges

in the application of

evidence to practice,

including lack of knowledge,

insufficient time to research

the knowledge, and

organisational barriers...’

BARRIERS TO IMPLEMENTING

EVIDENCE IN PRACTICE

Evidence is of little benefit to the

patient unless it is implemented in

practice. There are many challenges

in the application of evidence to

practice, including:

Lack of knowledge

Insufficient time to research the

knowledge

Organisational barriers, such

as management support for

changing practice (see

practice

point box

).

›

Remember

In wound care, the amount of

level 1 evidence is small due to the

difficulty in comparisons as a result

of the number of patient variables

involved, such as underlying

comorbidities, wound aetiologies,

many of which require treatments

of the underlying condition, e.g.

offloading in patients with diabetic

foot ulceration.