8 JCN supplement

2018,Vol 32, No 2

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

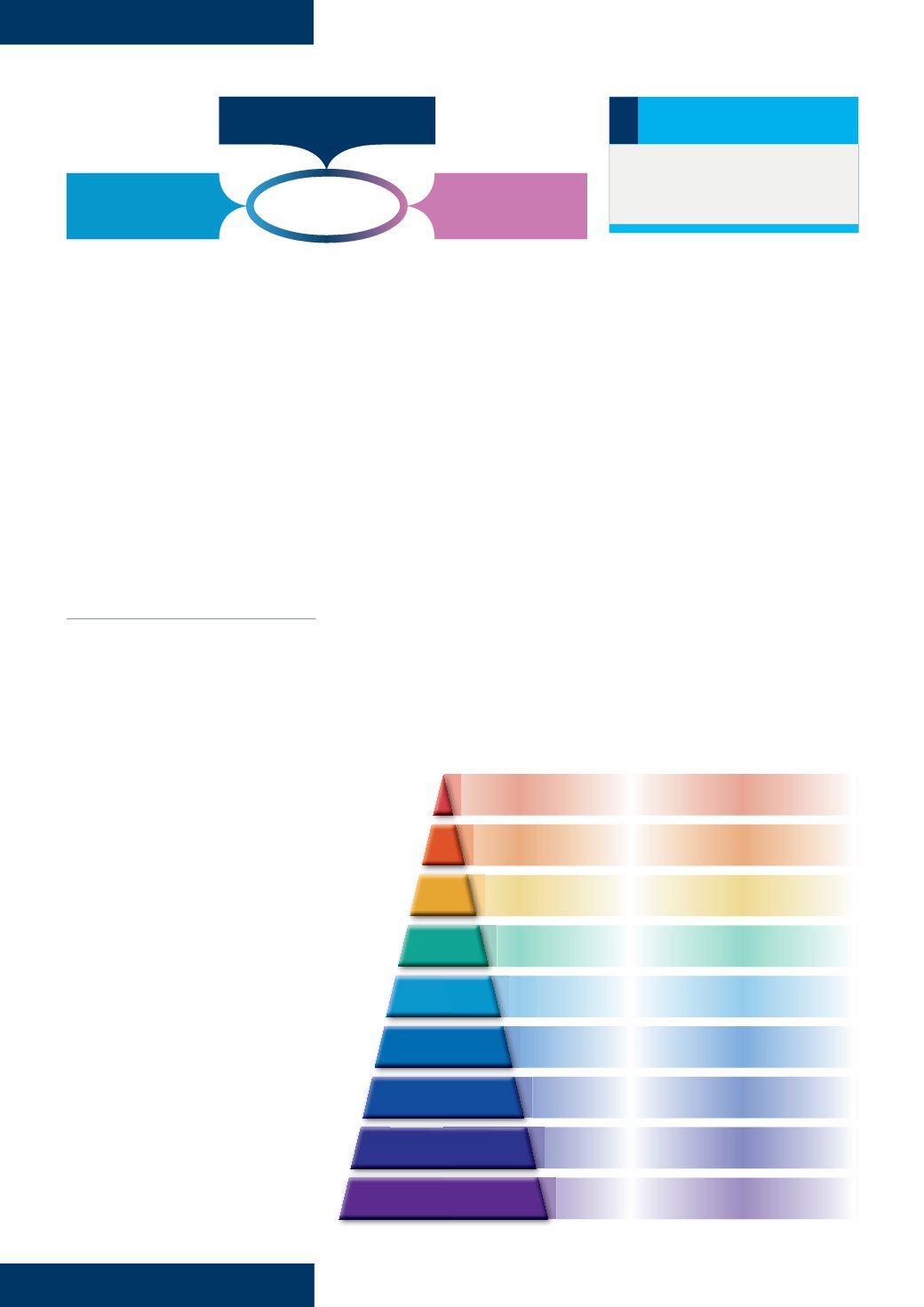

2011), and results of systematic

reviews that only take higher level

evidence into consideration. An

‘evidence hierarchy’ illustrates the

strength of the various types of

evidence (Figure 2), which

includes evidence from expert

opinion, non-experimental studies

such as qualitative and cohort

studies, experimental investigations,

including quasi-experimental

studies, randomised controlled trials

(RCTs) and systematic reviews of

RCTs (Borgerson, 2009; LoBiondo-

Wood and Haber, 2010).

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

Various levels of evidence exist to

guide nurses. Generally, the higher

the level of the evidence, the less

likelihood of bias in the results and

the more rigorous the research.

Where higher level evidence

exists in wound care, this should

be included in evidence-based

treatment protocols.

Low-level evidence

These include expert opinions

formed through the researcher’s

experience and observations, as

well as case reports and case series

(Guyatt et al, 2008). Because these

kinds of evidence comprise reports

of cases but do not feature control

groups to compare outcomes, they

have little statistical validity. In the

absence of higher level evidence,

case studies and expert opinion

can be used by clinicians to

determine the best wound care

interventions, albeit with variable

patient outcomes.

Moderate-level evidence

Non-experimental studies are

regarded as more robust than expert

opinion and can include longitudinal

or cohort studies, which are typically

observational in nature but lack

any manipulation of variables, such

as wound type, duration, and size

(Dearholt and Dang, 2012). Cohort

studies are not as reliable as RCTs,

as the researchers observe without

an intervention and the group are

not matched, whereas in an RCT you

have an intervention for one group

of patients, but the patients in the

non-intervention group are matched

as in age, wound type, etc. However,

cohort studies can complement

RCTs in that it is helpful to look at

what is happening in real life.

High-level evidence

The two types of evidence

considered to be the most valid

are systematic reviews and RCTs

(Roecher, 2012). RCTs are carefully

planned experiments that introduce

a treatment, as in a type of dressing

or bandage, to study its effect on real

patients. They include methodologies

that reduce the potential for bias

(randomisation and blinding) and

allow for comparison between

intervention groups and control, or

non-intervention groups. An RCT

is a planned experiment and can

provide sound evidence of cause and

effect, but they can take considerable

time and are costly.

Systematic reviews focus on

a clinical topic and answer a

specific question. An extensive

literature search is conducted to

identify studies that have a sound

methodology. The studies are

reviewed, assessed for quality, and

the results summarised according

to the predetermined criteria of the

review question. A meta-analysis

will thoroughly examine the studies

identified in the literature search

and mathematically combine the

results using an accepted statistical

methodology to report the results

(Dissemond et al, 2017).

i

Practice point

The higher the level of evidence,

the more robust the findings and the

more relevant to the patient group.

Figure 1.

Components of evidence-based care (EBP=evidence-based practice).

Figure 2.

Hierarchy of evidence.

Clinical expertise

Best research

evidence

EBP

Patient values and

preferences

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Double-blind randomised controlled trials

Meta-analysis and systematic reviews

Randomised controlled trials

Non-comparative clinical trials

Cohort studies

Case series or studies

Individual case reports

8

Animal research,

in-vitro

studies

9

Best practice statements, consensus panels,

expert opinion