COMMUNITY WOUND CARE

JCN supplement

2015 Vol 29 No 5

7

An example of a typical

intervention is ensuring that

patients are nursed on supports

surfaces that are appropriate for

their needs — here the ‘S’ of the

SSKIN bundle should act as a

prompt for nurses to ensure that

the patient is ‘stepped-down’ from

an active mattress to a static foam

mattress for instance.

Similarly, the ‘K’ for ‘keep

moving’ is there to remind nurses

that patients may require help

with changing their position, and

the frequency of this should be

decided by the trained member of

staff on each shift. For instance, a

patient may require fewer changes

of position during the day if they

are undergoing physiotherapy or

occupational therapy. This care

bundle serves to ensure that key

areas of care are covered to aid

prevention in those patients who

are at increased risk of developing

pressure damage.

James et al (2010) reported a

pressure ulcer prevalence of 26.7%

across community hospitals in

Wales — following introduction

of the SSKIN bundle the rates

subsequently fell (Keen and

Fletcher, 2013).

However, in those patients

who have already developed tissue

damage, pressure ulcers can give

rise to significant healing challenges

for clinicians. Category two, three

and four pressure ulcers all require

extensive dressings due to loss of

tissue, along with offloading —

where the area is ‘floated’ using

pillows or by supporting the leg

with devices usually supplied via

occupational therapy — as well as

regular changes in position.

Supplementary dietary intake

may also be required for those

patients whose nutritional needs

have been compromised.

Dressings can range from a

simple hydrocolloid that might

be used to cover a category two

pressure ulcer (Fletcher et al, 2011),

to the use of an alginate dressing

covered with a secondary covering in

a category four ulcer.

foot ulcers and, to a lesser extent, leg

ulcers. The edges of cavity wounds

must be protected, and dressings

used to assist healing from the

base of the wound upwards. This

ensures that there is no ‘undermining’

around the wound edges and that

the optimum tensile strength of the

wound is achieved.

Cavity wounds can be managed

effectively within a community

hospital setting, either with the

more traditional approach of lightly

packing the wound space or by using

topical negative pressure (TNP).

Dressing choice should be

discussed with the patient and

their individual health status taken

into account. By following a logical

pathway an updated plan of care

can be achieved, which should

enhance the patient’s ability to

move through to wound healing

(Harding et al, 2007) (

Figure 2

).

PRESSURE DAMAGE

Pressure damage is known to be

painful and distressing for patients

as well as costly for the NHS, both in

terms of occupied bed days and also

in compensation payouts resulting

from litigation (Bennett et al, 2004).

The introduction of SSKIN

bundles within community hospitals

demonstrated how planned

interventions can make a significant

difference to patients and the care

they receive. SSKIN is the acronym

for

`

6

upport surface

`

6

kin inspection

`

.

eep moving

`

,

ncontinence

`

1

utrition.

Adherence to local wound care

formularies and working with tissue

viability specialist nurses is crucial

when trying to decide on the most

appropriate product.

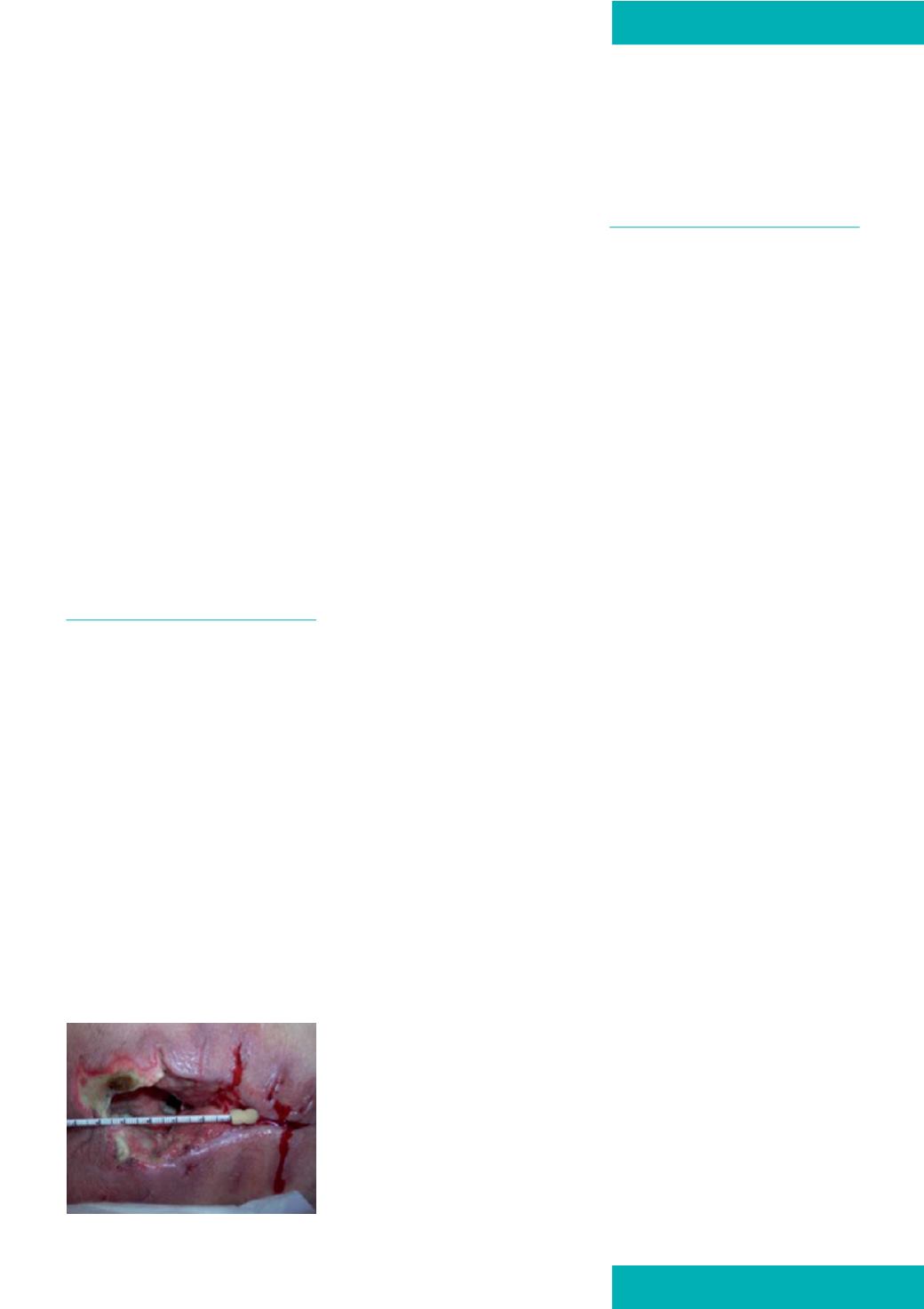

INFECTED SURGICAL WOUNDS

Surgical site infection (SSI) occurs

within a wound following either

keyhole or open surgery (National

Institute for Health and Care

Excellence [NICE] 2008), and is

usually identified by localised pain

at the wound site, heat, pyrexia and

tachycardia (Cutting and White,

2005). SSI rates are closely monitored

by infection prevention teams.

The first line of treatment in SSI

is a course of antibiotics, however

in severe cases the original surgical

incision site may dehisce — this

is where the wound itself has

insufficient strength to withstand the

forces placed upon it and the edges

come apart (

Figure 3

) (Bale and Jones,

2006). This can happen at any time,

but usually takes place between 6–10

days postoperatively and requires

further surgical intervention, which

may include debridement and

reclosure or localised debridement

with the wound then being left open

to close by secondary intention.

This kind of intensive long-term

treatment may not be appropriate in

the patient’s home and, particularly

bearing in mind the increased

cost of extra days spent in hospital

(Coello et al, 2005), the community

hospital could offer a safe and cost-

effective alternative.

Many wounds that have

dehisced due to infection present

with a cavity, which needs to heal

by primary intention from the

base upwards. Once they have

been packed and redressed daily,

many dehisced wounds are then

treated with TNP, which is able

to manage the large volume of

exudate associated with wound

infection. TNP also facilitates rapid

wound closure, as well as improving

patients’ quality of life by reducing

the number of dressing changes.

Although in the past TNP was

regarded as too expensive and only

Figure 3.

A typical dehisced wound.