COMMUNITY WOUND CARE

6

JCN supplement

2015,Vol 29 No 5

Each patient’s wound is affected

by physical and psychological

elements, as well as social factors.

Previously diagnosed health issues

such as diabetes are known to mask

problems such as wound infection.

The patient must be supported

to maintain their diabetes at the

optimum level to gain the positive

effects of wound healing (European

Wound Management Association

[EWMA], 2008).

The negative effects of smoking

on general health have been well-

documented in the past (Silverstein,

1992), specifically in wound healing.

As well as referral to mental

health services, these patients need

supportive wound care and advice

as to how to prevent or manage any

infections. Ousey and Ousey (2010)

have reminded practitioners that

those patients who self-harm must

have a holistic wound assessment

that includes questions about their

preferred treatments. It may be that

patients will continue to delay wound

healing, however if they are supported

by the whole healthcare team, long-

term harm may be avoided.

CHRONIC WOUND CARE

Where wounds have become

senescent and are failing to heal,

admission to a community hospital

allows for the wound to be re-

assessed and a differential diagnosis

made. Drew et al (2007) suggested

that up to one-in-three chronic

wounds remained unhealed for at

least six months, and one-in-five

for a year or more. This is not to say

that district nurses are unable to

manage patients’wounds effectively;

rather that placing patients in a

more appropriate care setting means

procedures can be undertaken

more efficiently.

Chronic wounds can lead to:

`

Increased risk of infection

`

Psychological stress

`

Impaired skin function

`

Odour

`

Reduced nutritional status

`

Sub-optimal clinical and

cosmetic outcome.

Cavity wounds

Cavity wounds are a common type

of chronic wound that often develop

as a result of pressure ulcers, diabetic

Nicotine is a vasoconstrictor that

reduces the nutritional blood flow to

the wound and surrounding tissues,

resulting in ischaemia and impaired

healing. Patients who smoke can

be offered alternatives to nicotine

and referral to smoking cessation

specialists while in hospital.

Wounds need nourishment to

heal and older patients may have

difficulty maintaining the adequate

dietary intake required. Timms

(2011) advised early identification

of patients at risk of poor nutrition

and referral to dietitians. While it is

important that patients’ nutritional

needs are assessed while they are

still in hospital, it is also necessary

to consider how sufficient nutrition

will be provided on discharge.

In some cases, patients may

inflict their own wounds. Known

as factitious wounds, these injuries

can be unusual in presentation and

fail to heal whatever treatment is

used. Self-harming is a behaviour

not an illness, and the cause of the

patient’s distress will need to be

investigated by the mental health

team. Self-harm is a problem that

is being increasingly recognised

in ex-military personnel and

unfortunately the UK has the

highest numbers of people across

Europe that self-harm (Royal

College Psychiatrists, 2010).

To a degree, a ‘non compliant’

older person with a long-term leg

ulcer might be considered to be

self-harming if they continued to

sabotage treatment to retain a level

of communication with healthcare

staff, for instance.

Careful monitoring of the

patient’s environment may indicate

how the wound was inflicted.

Various techniques can be used to

either create a wound or ensure

that it remains open. In the author’s

clinical experience, these can

include washing wounds in bleach

(this presents as highly excoriated

and painful periwound skin) and

even setting fire to the bandages/

dressings. Scissors, razor blades,

pens and cigarettes have also been

used as ways of maintaining a

wound (Corser and Ebanks, 2004).

i

Practice point

:RXQGV QHHG QRXULVKPHQW WR

KHDO DQG ROGHU SDWLHQWV PD\

KDYH GLIÀFXOW\ PDLQWDLQLQJ WKH

DGHTXDWH GLHWDU\ LQWDNH UHTXLUHG

(DUO\ LGHQWLÀFDWLRQ RI SDWLHQWV DW

ULVN RI SRRU QXWULWLRQ DQG UHIHUUDO

WR GLHWLWLDQV LV LPSRUWDQW :KLOH

LW LV LPSRUWDQW WKDW SDWLHQWV·

QXWULWLRQDO QHHGV DUH DVVHVVHG

ZKLOH WKH\ DUH VWLOO LQ KRVSLWDO

LW DOVR QHFHVVDU\ WR FRQVLGHU

KRZ VXIÀFLHQW QXWULWLRQ ZLOO EH

SURYLGHG RQ GLVFKDUJH

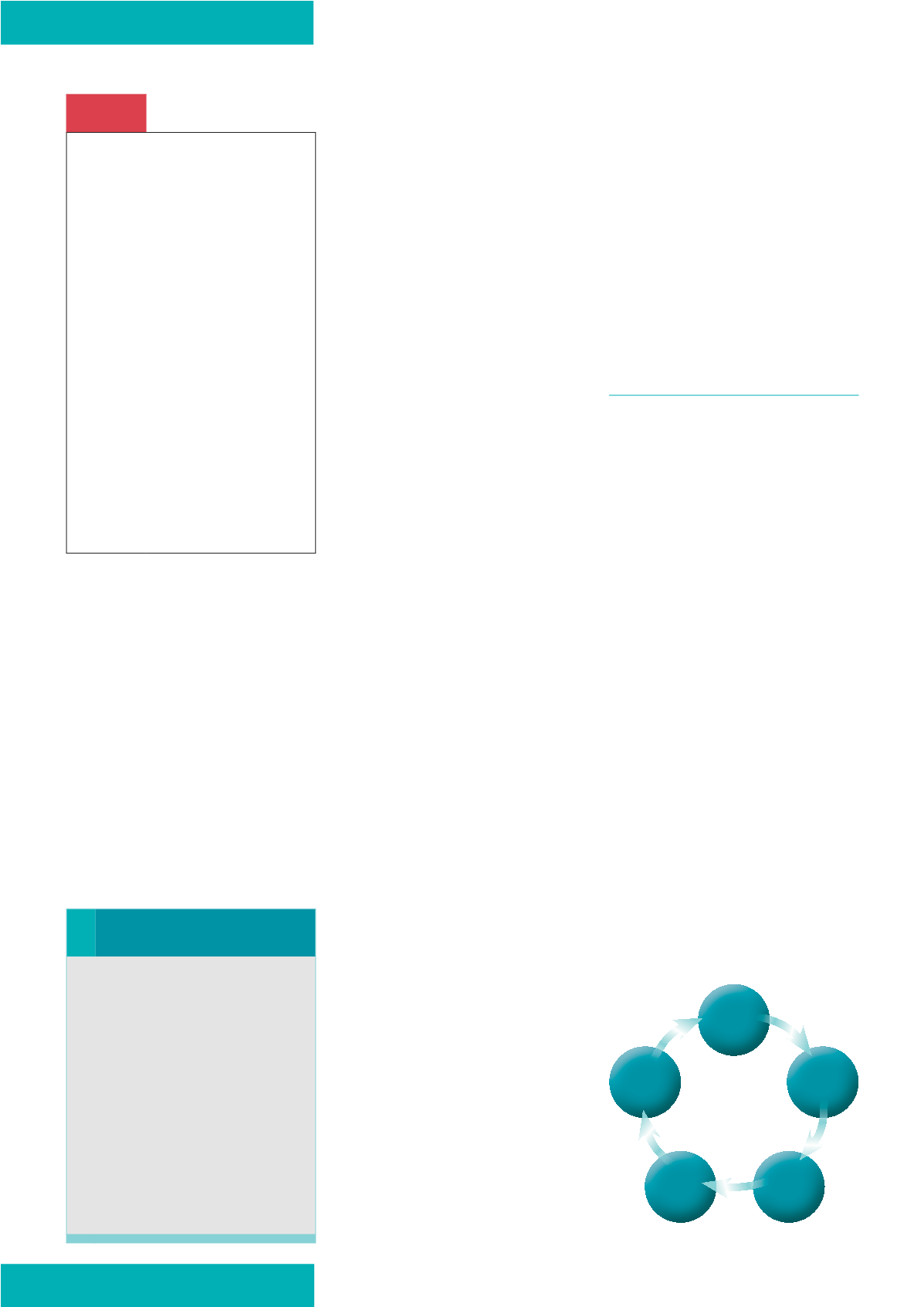

Figure 2.

A typical pathway of care.

Red Flag

Infection

:RXQG LQIHFWLRQ UHVXOWV IURP

WKH LQDELOLW\ RI WKH SDWLHQW·V

ERG\ WR FRQWURO WKH EXUGHQ

RI EDFWHULD ZLWKLQ D ZRXQG

,GHQWLI\LQJ WKRVH IDFWRUV ZKLFK

LQFUHDVH WKH OLNHOLKRRG RI

LQIHFWLRQ DQG PD[LPLVLQJ WKH

SDWLHQW·V QDWXUDO GHIHQFHV DUH

HVVHQWLDO VWHSV LQ SUHYHQWLQJ

LQIHFWLRQ ,I LQIHFWLRQ RFFXUV LW

LV LPSRUWDQW WKDW FOLQLFLDQV DUH

DEOH WR LGHQWLI\ WKH VLJQV DQG

V\PSWRPV DQG LQLWLDWH VSHHG\

DQG DSSURSULDWH WUHDWPHQW

-XGLFLRXV XVH RI WRSLFDO

DQWLPLFURELDO ZRXQG GUHVVLQJV

KDV SURYHQ WR EH DQ HIIHFWLYH

PHWKRG RI UHGXFLQJ ELREXUGHQ

DQG HQDEOHV FOLQLFLDQV WR UHVHUYH

WKH XVH RI DQWLELRWLFV IRU WKRVH

SDWLHQWV LQ JUHDWHVW QHHG

History

Investigation

Diagnosis

Indicators

(for progress)

Examination