32

WOUND CARE TODAY

2017,Vol 4, No 1

FOCUS ON

M

OISTURE

i

Top tip:

Exudate is a good indicator of the

state of a wound. Changes in colour,

amount, viscosity or smell can be a

trigger to reassess the wound.

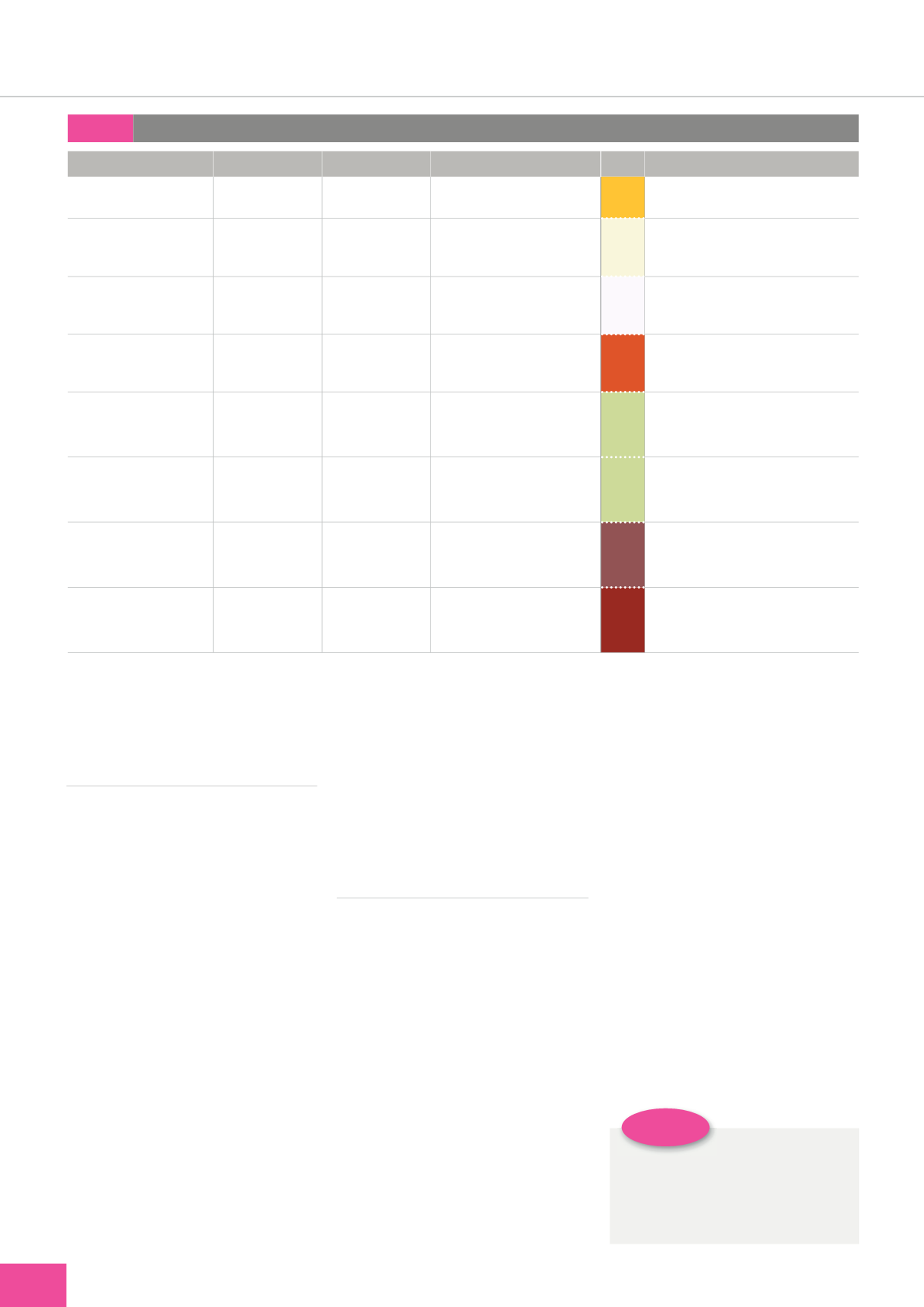

Table 1:

Exudate assessment (adapted with permission from Cutting, 2004)

Underlying cause

Type

Volume

Description

Interpretation

Acute injury to superficial

or partial-thickness wounds

i

Serous

i

Low–moderate

i

Clear, thin, watery, amber-

coloured exudate

i

Inflammatory exudate normal

within the first five days of acute injury

Acute injury with presence

of bacteria or superficial

non-viable tissue

i

Fibrinous

i

Low-high

i

Creamy, cloudy, thin

exudate with the presence of

fibrin protein strands

i

Inflammation or local infection

Acute injury, post

operatively or trauma on

dressing removal

i

Serosanguinous

i

Low–moderate

i

Clear, watery, thin, pink-

coloured exudate

i

Inflammatory exudate with mild

capillary damage

Acute injury, post

operatively or trauma on

dressing removal

i

Sanguinous

i

Low–moderate

i

Watery, thin, red-coloured

exudate

i

Trauma to blood vessels

Chronic wound with non-

viable tissue present

i

Seropurulent

i

Moderate–high

i

Yellow/grey/green, thick

exudate

i

Local or possibly

spreading infection.

Liquefaction of

necrotic sloughy tissue

Acute wound dehiscence or

chronic wound with non-

viable tissue

i

Purulent

i

Moderate–high

i

Yellow/grey/green, thick

exudate

i

Indicative of bacterial infection, e.g.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Acute wound dehiscence or

chronic wound with non-

viable tissue

i

Haemopurulent

i

Moderate–high

i

Viscous, thick, sticky red/

brown exudate

i

Confirmed spreading infection

Acute deep wound trauma

or chronic wound with

extensive non-viable tissue

i

Haemorrhagic

i

High

i

Thick, dark red exudate

i

Vessel damage from trauma or

chronic wound infection. Capillaries

are friable and spontaneously bleed

tissue, a large volume of bacteria in

the wound and malodour (Wounds

UK, 2013).

NEGATIVE IMPACT

OF WOUND EXUDATE

The presence of wound exudate can

be the most distressing aspect of

having a wound for an individual

and their carers. The impact of

copious exudate and odour on the

individual’s quality of life in many

cases is intolerable, and empirical

evidence demonstrates heightened

anxiety, depression, embarrassment

and social isolation in patients with

wet, malodorous wounds (Franks

et al, 2003; Eagle, 2009; Meaume et

al, 2017). Tissue damage resulting

from exposure to exudate, such as

maceration and excoriation (see

practice point boxes

) causes pain,

discomfort and delayed healing

(Whitehead et al, 2017).

In addition to the negative

impact on patient quality of life,

exudate can result in significant

expense as a result of attempts

to mask odours and contain the

fluid. Protective sheets and towels,

replacement bedding, footwear or

clothing and increased washing

may be necessary where exudate

is uncontrolled, which is time-

consuming and distressing for

patients and carers. And, indeed,

can be challenging for those

patients who are physically less able

(Tickle, 2016).

LOCAL WOUND ASSESSMENT

Moisture is required by the wound

throughout the wound healing

process. It promotes the natural

autolysis of devitalised tissue in

the destructive phase of healing

and enhances epithelialisation

in the latter stages (Dowsett and

Newton, 2005). However, there is a

subtle balance between the wound

bed being too wet or too dry; a

dry wound will have reduced cell

proliferation, while a wet wound

will have non-viable macerated

cells preventing epithelialisation

from the wound edge (Myers, 2012).

Both sets of conditions will result in

delayed healing which increases the

risk of local and systemic infection.

While acute wound exudate

is a normal response within the

inflammatory stage of healing,

chronic wound exudate is either

a symptom of a local problem

with the wound, such as critical

colonisation, biofilm formation or

infection, and/or results from an

underlying condition such as venous

disease, oedema, hypoalbuminaemia

or organ failure.

Establishing why the wound

is producing copious exudate is a

prerequisite to establishing effective

treatment goals for the individual.

Consequently, as part of holistic

wound assessment, the volume,

colour, consistency and odour of

exudate should be evaluated and

recorded, along with its effects, if

any, on the skin surrounding the

wound (WUWHS, 2007)(

Table 1

).