PALLIATIVE WOUND CARE

Top tip:

The patient’s comfort should

always take priority over any

wound care or measures to

prevent skin breakdown.

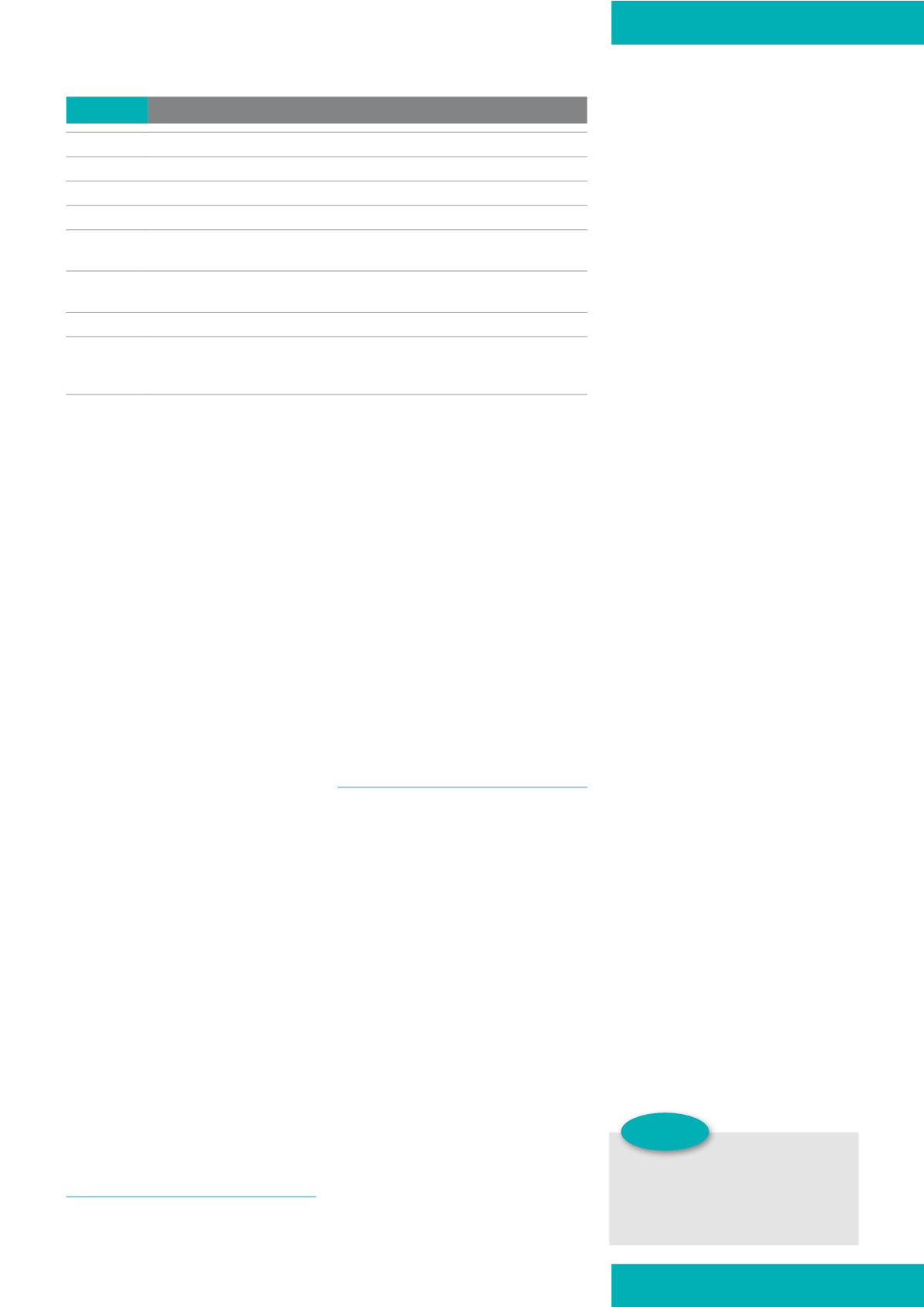

Table 1:

3ULQFLSOHV RI SDOOLDWLYH FDUH :RUOG +HDOWK 2UJDQL]DWLRQ >:+2@

`

It provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms

`

It affirms life and regards dying as a normal process

`

It intends neither to hasten nor postpone death

`

It offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death

`

It offers a support system to help the family cope during the person’s illness and in their

own bereavement

`

It uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement

counselling, if required

`

It enhances quality of life, and can also positively influence the course of the illness

`

It is applicable early in the course of illness, together with other therapies that are intended to prolong

life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better

understand and manage distressing clinical complications

JCN supplement

2015,Vol 29, No 5

15

[BDNG], 2012) (barrier products

are further discussed below under

‘maceration and excoriation’).

Radiotherapy burns, that can

occur in cancer patients, may be

helped by the application of gels

and specific foam products which

contain moisturisers (Princess

Royal Radiotherapy Team/St James’s

Institute of Oncology, 2011).

Pruritis, or itch, is sometimes

seen in palliative care. This skin

sensation can be distressing and

have a negative impact on quality of

life, with some patients even finding

pain preferable to pruritis (Zylicz,

2004). It is a difficult symptom to

manage and is largely unresponsive

to antihistamines. However, tricyclic

antidepressants may offer some

relief, while non-pharmacological

interventions, such as transcutaneous

electrical nerve stimulation (TENS),

are reported to offer some benefit

(Grocott, 2007).

Skin inspection should occur on a

daily basis, although changes noted in

the patient’s condition may increase

or decrease the frequency. All findings

from regular reassessment of the

patient’s skin should be documented

and form part of holistic care.

Educating patients and their families/

carers about the significance of skin

observation and reporting any redness

promptly is also vital to help prevent

skin breakdown (McManus, 2008).

WOUND MANAGEMENT

Care planning should be the result

of thorough patient assessment,

including psychological aspects,

and consider:

`

The patient’s personal history,

social circumstances

and understanding

`

Clinical assessment, i.e. the

patient’s illness, symptoms,

treatment and current

management

`

Wound assessment, i.e. the

site, size, tissue types present,

condition of the wound bed and

periwound skin, exudate, pain,

odour, and bleeding

`

The family’s/carer’s concerns,

expectations, etc

`

The patient’s wishes, concerns

and priorities.

WOUNDS TYPES

In the author’s clinical experience,

the two main categories of wounds

encountered in palliative care are

pressure ulcers and malignant wounds.

Pressure ulcers

Patients with palliative care needs

are at significant risk of developing

pressure ulcers (Stephen-Haynes

2014) as a result of:

`

Increased age

`

Reduced mobility and activity

`

Poor nutritional status

`

Exposure to friction and shear

`

Exposure to moisture (Langemo

et al, 2010).

Prevention of pressure ulceration

includes risk assessment, re-

positioning, nutritional assessment/

management, continence

management and the use of pressure-

relieving equipment, including

bed-bases, mattresses and cushions,

to help minimise the negative impact

that having a pressure ulcer can have

on the patient’s physical, emotional

and social life (European Pressure

Ulcer Advisory Panel/National

Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel/

Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance

[EPUAP/NPUAP/PPPIA], 2014;

National Institute for Health and

Care Excellence [NICE], 2015).

Malignant wounds

Malignant wounds are caused

by the invasion of skin tissues

and supporting blood and lymph

vessels by cancer cells (Pearson and

Mortimer, 2004). These may be:

`

Locally advanced

`

Metastatic

`

Recurrent.

As the tumour extends, the

angiogenesis development of

the blood capillaries becomes

disordered altering the blood clotting

mechanism within the tumour

(Collier, 2000).

Grocott (2007) observed that

primary cancers such as breast, head,

neck, colon and penis more commonly

fungate. Fungating breast cancer can

appear as deep necrotic ulceration

with proliferative growth of the ulcer

margins, while cancer of the ovary,

caecum and rectum, which infiltrate

the anterior wall of the abdomen,

present as small raised nodules,

developing into necrotic‘cauliflower-

like’structures (Grocott, 2007).

It is essential that care includes

treatment of the underlying tumour,

management of comorbid conditions,

and symptom management.

Specific aspects relating to tissue

viability in palliative wound care

include maceration and excoriation,

malodour, infection, bleeding

and pain.

Maceration and excoriation

The nature of wounds occurring