42

WOUND CARE TODAY

2017,Vol 4, No 1

FOCUS ON

E

DGE

i

Remember:

Epithelial advancement is a

clear indication that a wound

is healing.

result in reduced perfusion, which

damages surrounding tissues and

prevents the creation and attachment

of new skin cells (Dowsett and

Newton, 2005; Leaper et al, 2012).

TREATMENT

To promote wound edge progression,

clinicians must establish a differential

diagnosis and offer treatment

that addresses the underlying

cause of the wound, for example,

correcting venous hypertension with

compression in patients with venous

ulceration (O’Meara et al, 2012;

Ashby et al, 2014 ), or offloading of

the diabetic foot. Furthermore, it is

essential that the chosen treatment

addresses local wound symptoms

identified in

Table 1,

as otherwise

patients may struggle to concord with

treatment (Price, 2013).

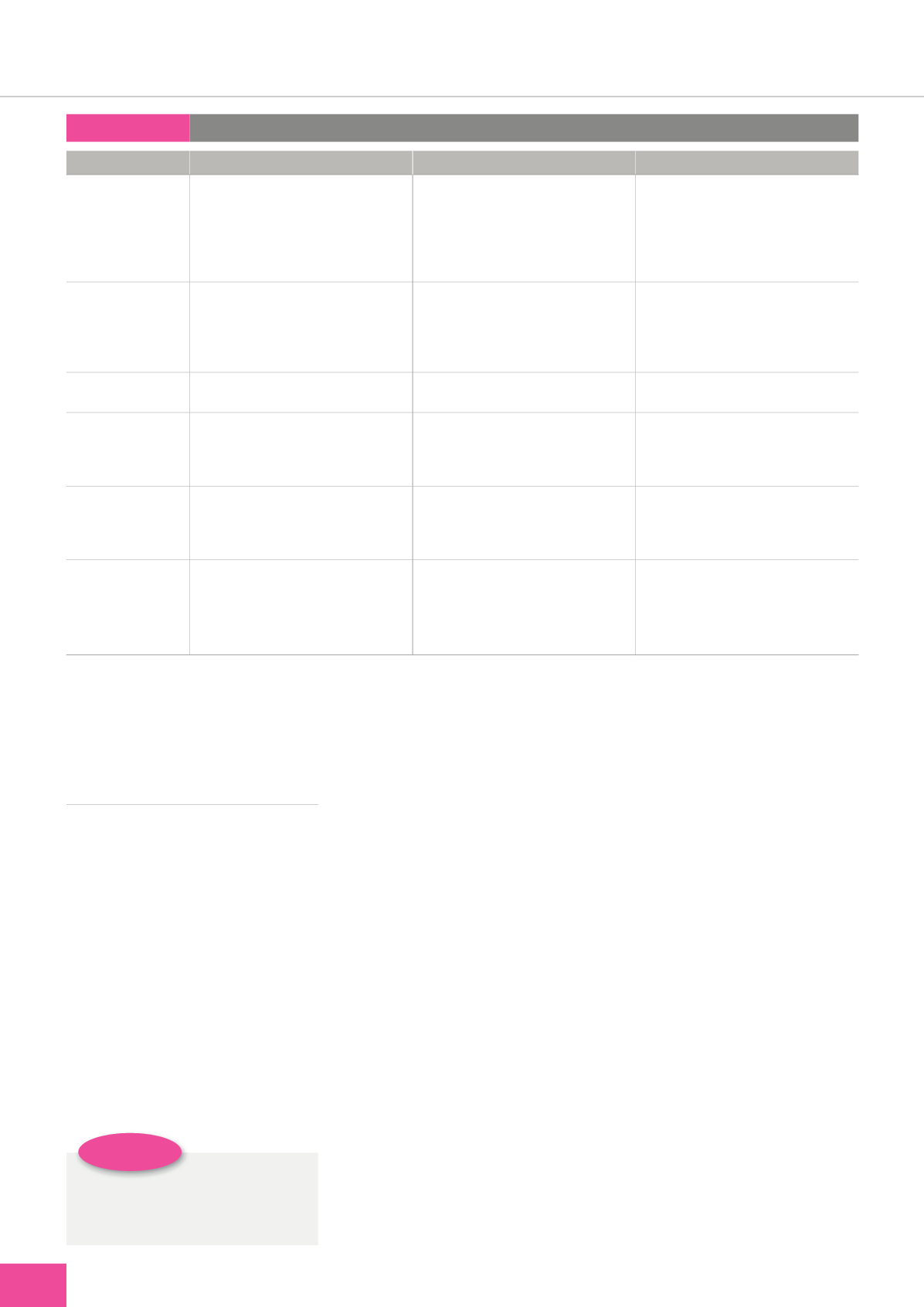

Table 1:

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation

Description

Clinical impact

Treatment options

Maceration

Environmental damage from excess volume

of exudate left on the periwound skin, as the

enzymes break down the stratum corneum

Periwound extension

Inflammation

Skin susceptible to damage from trauma

Exudate management

Treatment that addresses the underlying cause of

the wound and thereby minimises the volume

of exudate

Compression

Absorbent dressings

Excoriation

Environmental damage/loss of skin from abrasion Inflammation

Pain

Skin susceptible to damage from trauma or skin

stripping from exudate and adhesives

Skin protection with barrier products, adhesive

removers/silicone adhesives

Papillomatosis

Skin surface elevation caused by hyperplasia and

enlargement of the dermal papillae

Reduced hydration and inelasticity

Diagnosis of underlying condition

Emollients to maintain elasticity and hydration

Hyperkeratosis

Thickening of the stratum corneum (outermost

layer of skin) secondary to chronic inflammation

Excess development of the stratum corneum or

delayed exfoliation

Dryness

Fissures

Diagnosis of the underlying condition

Debridement cloths

Emollients

Callus

Localised thickening of the epithelium because of

pressure or friction

Increases pressure

Can lead to sub-callous ulceration

Prevents accurate assessment

Prevents epithelial migration

Offloading

Sharp debridement

Eczema/dermatitis

Irritation of the skin secondary to inflammation,

caused by underlying pathology or application

of allergens

Erythematous, small blisters, weeping and crusting

Often itchy

Can lead to scratching and hyperkeratosis

Diagnosis of the underlying cause

Treatment targeted at underlying pathology

Avoid common irritants

Simple emollients to rehydrate the skin

Topical corticosteroids

It is common for patients to be

labelled as non-concordant when,

in fact, it is the clinician’s failure to

address symptoms, i.e. successful

diagnosis of the type of wound pain

and its management, or breaking the

itch–scratch cycle associated with

periwound eczema.

Critical to success is concomitant

treatment of underlying conditions

that negatively impact on healing —

often termed, optimising the host.

Examples of this may be addressing

nutritional deficiencies to achieve tight

glycaemic control and/or managing

underlying conditions, e.g. diabetes,

heart failure, autoimmune disorders,

that impact on the host immune

system. In tandem, prevention

of complications associated with

wounds, such as infection, excoriation

or maceration, is critical for patient

concordance and achieving positive

outcomes. Unfortunately, misdiagnosis

or having treatment for a wound of

unknown origin is not uncommon

(Drew, 2007; Guest et al, 2015; 2017).

Damaged periwound skin is

common in chronic wounds. It has

been linked to delayed healing, pain

and discomfort, and failure to address

issues can lead to extension of the

wound margins (Ousey and Cook,

2011). Thus, clinicians should protect

the periwound skin, establish the

correct cause and plan corrective care,

for example, minimising contact with

moisture or rehydrating dry tissue with

emollients. Managing excess exudate

is vital if clinicians want to reduce

the risk of periwound skin damage

(Dowsett et al, 2015). Excess moisture

can affect the barrier function of the

skin and is linked to continued skin

breakdown, maceration and dermatitis.

Chronic wound exudate is high in pro-

inflammatory mediators, and it alone

can be a wounding agent (Schultz et

al, 2003; Leaper et al, 2012).

Addressing the‘T’(tissue non-

viable) of TIME in relation to the use

of debridement of devitalised skin,

callus, necrosis and slough is also a key

component of encouraging migration

of the edge of the wound. Periwound

callus and scabs, i.e. hard plaques

of skin, can cause pressure when

the patient is walking or beneath

compression, and, as such, should be